The death of my grandfather in 2014 marked a significant change in my life. His burial rituals and, the customs and traditions that followed brought me numerous questions about the various practices we performed. Although I had always been a person engaged in political and social discussions, it was my lack of knowledge on religion and, culture and traditions, that was bothering me the most. I had so many questions and the answers to them were not available from my parents. Hence, to unearth the dimensions of my religion and culture, I aimed to undertake a tour of the renowned Shrine of Hazrat Data Ganj Baksh Hajveri. The Shrine is famously known as the “Data Darbar”.

A view of Data Darbar (Nawaz, 2014)

To begin with, I was already living in a city which was one of the, if not the most, famous Punjabi cultural region in Pakistan. Pre-independence, the town used to be a hub where Muslims, Sikhs and Hindus used to practice their culture and faith freely. The Punjabi Culture, however, dominated Lahore more than the individual religions did.

Lahore is home to many significant sacred spaces like the Shrine of Hazrat Data Ganj Baksh Hajveri (for Muslims) and the tomb of Maharaja Ranjit Singh (for Sikhs). My adherences, however, were more inclined towards Hazrat Ganj Baksh. My first objective was to visit the Shrine and study the spread of Islam in the subcontinent by saints such as Hazrat Ganj Baksh.

The Shrine is deemed to be a place as it renders a context in which everyday knowledge and experience are collected. Moreover, it provides a framework for the processes of socialization and structures the everyday routine of people’s economic and social life.

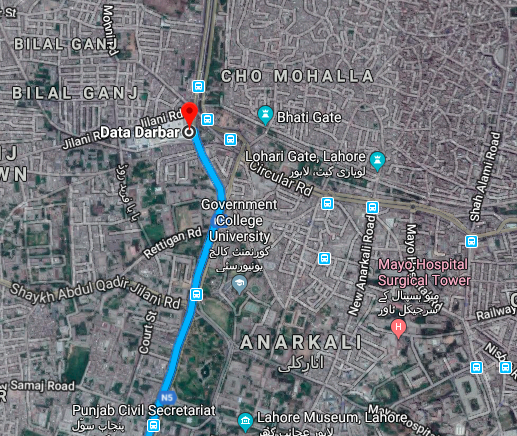

The nominal location of the place is Data Ganj Baksh Shrine. The absolute location of the Shrine is Longitude 31.579237 and Latitude 74.305870 (Google Maps, 2018). The relative location of the shrine is East of Bhatti Gate, another historical site and north of Anarkali, the primary market of old Lahore (Google Maps, 2018). On my first visit, I learned that reaching Bhatti Gate would quickly lead you to the Shrine as you notice the minarets of the mosque adjacent to it, this provided the cognitive location of the Shrine that I developed during my visits. Hence, one can simply take the road straight from the Bhatti gate which leads directly to the Shrine.

Bhati Gate and Anarkali shown relative to Data Darbar in Google Maps (GIS)’s Satellite imagery. (Google Maps, 2018)

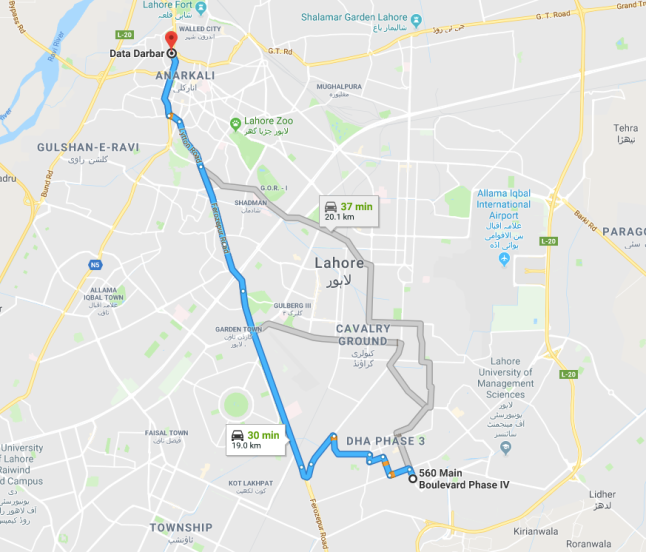

For a person coming to the old part of the city from the new part, the distance is huge. The absolute distance to the Shrine from my home is about 20 km whereas the relative distance is easily half an hour to an hour, depending on the traffic (Google Maps, 2018). Considering the rush of old Lahore and its narrow streets, going to the Shrine used to take a lot longer than coming back from the shrine, this was the cognitive distance that I grasped. It used to take so long that I used to sleep in the back of the car. The social distance, however, was the largest as most of the custodians of the Shrine and the people praying at the Shrine were dwellers of the peripheral region of Lahore. I, on the other hand, came from the core region, that is the new part of Lahore.

Location, distance and time from my Residence to Data Darbar given by Google Maps (GIS). (Google Maps, 2018)

My accessibility to the area was comfortable. I had a car available on Wednesdays for this particular task, so my accessibility to that area was convenient, however, in the walled city I had to walk plenty because of the narrow streets. The language spoken and the customs of the people were similar to that of mine, so communication was never a problem for me. Moreover, as the Shrine was open for everybody, of every religion or culture, there was no problem in reaching the site.

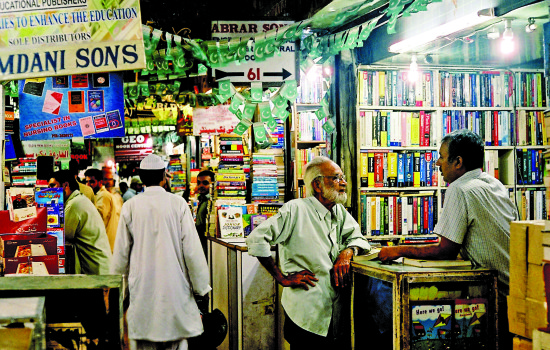

My utility, however, was the main point. I learned the history of Hazrat Ganj Baksh and his teachings not only from the books that I had bought from Anarkali (the central market of Old Lahore), but also from the people discussing the subject in different corners of the Shrine, sometimes them being scholars or custodians of the Shrine.

Being a person who has always been patriotic about his nation, I was more involved with the Urdu language as it is the national language. I never actually placed any heed to Punjabi, though in my household, Punjabi was the dominant language. However, at Data Darbar, my new bond with the people was based on the cultural language, Punjabi. The Punjabi poetry recited were ones composed during the 9th century by the Saint himself and his followers. The difference in the Punjabi language was evident, and one could realise how the language had changed over time. It was a realisation I felt most when what was being said went over my head even though I considered myself fluent in the language. When I brought back the poetry home, my parents could interpret it but, with some difficulty. They would explain to me that Punjabi has changed considerably in the last 50 years, let alone since the 9th century.

Though religious and cultural books remained the core of my studies, these experiences played a vital part for me in realising about the legacy of my religion and culture. The interdependence between my home, and book market, and the Shrine was apparent.

Through these experiences, I was able to supply the demand for a different type knowledge and understanding that I had recognized were missing from the books that I was reading and the discussions I was having with my parents. My family, filled with people of high caliber, were not able to answer questions that those usual, sometimes uneducated, people at the Shrine were able to resolve. Though the cost of fuel and time was immense, it was worth it in a sense that I had never felt more connected to my religion and culture. Hence the transferability cost was low. Moreover, in this way, I was able to discover many hidden aspects of Lahore that I had never seen, even after being in Lahore for more than ten years. Amongst them, the most important discovery was that of Urdu Bazaar. Urdu Bazaar was an intervening opportunity that I came across in my visits to the Shrine, a sea of high-grade books at a very fair rate.

Urdu Bazaar in Old Lahore. (Anjum, 2015)

In the Old Lahore, unlike the New one, everyone here was incredibly passionate and connected to there history and culture. Knowledge of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, a figure not well-revered amongst Muslims, was even very much recognised and understood by the people.

The knowledge of religion and culture that I had gained was hierarchical diffused from me to my family who had long since dropped the understanding of our Islamic religion and Punjabi culture. Regular discussion about my experiences became a part of our conversations during Ramazan, a sacred month in Islam, and it was 6-months after I had first visited the Shrine that a group of my cousins decided for us to go to Multan, the city of Saints. Through the push I had received from the experiences at the Shrine, my interest regarding culture and religion increased. Hence, to discover more, Multan was to be my next destination.

To conclude, amongst the various things in which the Shrine tour affected me, the knowledge and understanding of culture and religion gained through discussions and experiences such as traditional Punjabi poetry or religious chants were the most critical ones. On the other hand, amongst the ways in which I affected the place was not only the knowledge and understanding I illustrated and discussed in group settings, that I had gained from books, but also other rather factors too, such as giving money for various donations at the Shrine and buying things, most important books, from the old Bazaar nearby.

Multan is a cultural region of its own due to its mixture of Punjabi, Sindhi and Siraiki culture. Since before independence, it has been a hub for Sufi Muslims, paying respects to the various Saints that rest here.

Multan is also judged to be as a place, just like Lahore, as it provides setting for social interactions. Multan holds all the determinants that make the Shrine in Lahore a place with the addition that it provides opportunities and constraints to people.

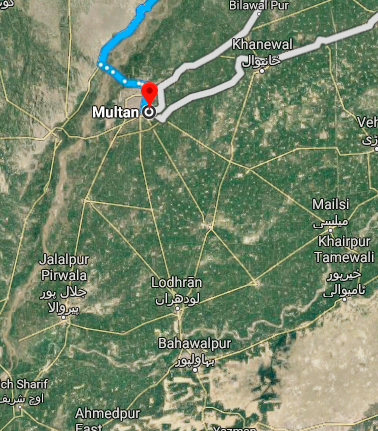

The nominal location of the place is Multan. The absolute location of Multan is Longitude 30.159195 and Latitude 71.525292 (Google Maps, 2018). Multan’s relative location is Southern part of the Punjab province, near the old-princely city of Bahawalpur. It is not so far from Bahawalpur, being on the main G.T Road leading to the old-princely city, North to Bahawalpur and West to Khanewal (Google Maps, 2018). When the lush vegetation of central Punjab ends and the desert zone starts, you are entering Multan. This was the cognitive location that I constructed in identifying when we came to Multan.

Location of Bahawalpur and Khanewal relative to Multan shown by Google Maps (GIS)’s satellite imagery. (Google Maps, 2018)

The journey to was Multan horrible. The absolute distance is about 350 km, and the relative distance is 6 hours (Google Maps, 2018), one of the reasons why travelling to Multan always felt like a huge burden. The cognitive distance to Multan seemed to be endless perhaps due to the presence of deserts near Multan that makes one pessimistic of the trip, however, when leaving Multan, not so much, again due to the reason of vegetation. Here, the social distance was vast, even more than Lahore, due to factors such as food, language and dressing as I was to discover later. An important factor would be Multan being a semi-peripheral region while Lahore being a core region.

Location, distance and time from Lahore to Multan given by Google Maps (GIS)’s satellite imagery. (Google Maps, 2018)

Multan was highly accessible for us for multiple reasons. It only required a journey by car which, though was horrible, was affordable for us to undertake with costs such as fuel costs and car service costs. We were to stay at the residence of a local spiritual leader, known as ‘Pir’. Thus, our accommodation expenses were covered. Other than that, communication was not to be a problem as Multan being part of Punjab, Punjabi and Urdu were the dominant languages. Though, Siraiki, another language, was also a widely spoken, a language I had no clue about.

In Multan, the local Pir with whom we was staying was a custodian of the Shrine of Bahauddin Zakariya. Bahauddin Zakariya was known to have been a great Sufi Saint who had influenced a generation of Saints, most famous amongst them was Syed Usman Marvandi, known as Lal Shahbaz Qalandar (Lohar, 2004). Not only was I going to learn about the life of Bahauddin Zakariya, but also about the numerous saints whom he had influenced. Hence, high utility was apparent. Another useful detail was the fact that the Pir was highly educated about the life of the Baha-ud-Zakriya and his disciples and hence, was a reliable authority for information. Furthermore, he was able to give us special entrance to many parts of the shrine.

Shrine of Baha-ud-Din Zakriya. (FLICKR/SMDANISH, 2018)

The Shrine of Baha-ud-Zakkriya is the most famous sacred place in Multan. Moreover, it possesses the same cultural system as I had seen in Data Darbar. Men sitting around and discussing the poetry and life of the Saint. Food is also distributed here amongst the poor as was also done in Lahore. However, one of the things that I noticed was slightly different here was the change of dialect. Siraiki and Sindhi had influenced the Punjabi here to a certain extent and hence; it was different to what I had observed in Lahore. The Punjabi spoken at Lahore was more similar to the Indian one, something I would go on to realise later, than the Multani one. Amongst the various cultural traits that I observed were changed here, the most prominent was food. The food here was less spicy and more sweet than that in Lahore. Further, the dressing was also different with massive inclusion of traditional Sindhi Topi, a Sindhi cultural trait. This was different from what follows in Lahore where no caps or hats are worn.

Visitors at Data Darbar in Lahore. (Official, n.d.)

People of Multan at the Urs of Bahauddin Zakariya. (Express, 2015)

While Lahore possessed only Ganj Baksh as a famous Sufi Saint, Multan in comparison had six. Hence more supply of knowledge and experience was available here than even the demand of it I had in Lahore. Multan complemented Lahore to a rather large extent. In Lahore, you did not have a concept about Spiritual leadership or scholars who sat openly in the tombs. Hence, more knowledge was regularly spread here. Though the hot summers made it challenging to live in Multan, the transferability was worth it as I was able to visit not one, but six different shrines and was able to pray in scared spaces.

In between Lahore to Multan, I saw numerous villages and old places, but all of these I had already seen before, partly the reason why the travel was boring so, less or no intervening opportunities were exploited. By the end of my tour, I was capable enough to hierarchical diffuse a whole account of our culture and religion when I came back to Lahore. I was able to reconcile myself that the legacy of my culture and religion was not something to go comfortably on. It was something that people had made challenging to follow and implement, and it was partly because of that reason that people like me preferred to ignorant about it.

Just like in Lahore, here the Shrine too affected me by giving a more in-depth understanding of my religion and culture, introducing me to even a more different version of the Punjabi culture, something which I had never encountered. On the other hand, here I was able to confidently affect the area by discussing the life of Hazrat Data Ganj Baksh Hajveri and his teachings that I had learned in Lahore. We discussed his poetry and the ways in which the teachings of both Saints differed. Not only this, my Lahori dialect of Punjabi and fluency in Urdu (Persian influenced version which is not common in Multan) was something that majority took an interest in and were curious in learning and knowing about.

Shrine of Hazrat Baha-ud-Din Zakariya. (Abbas, 2016)

While I had finally reconciled myself with my religion and culture, a significant challenge emerged before me when my Canadian Visa came, and I was to travel to Burnaby, Canada for my university. I was pulled out of my small world to a larger, more diverse one. I got my admission into Simon Fraser University, and SFU Residence was now supposed to be new home. It was at SFU that I would meet challenges upon my culture and religion.

The centre hub of my discussions and interaction became the SFU dining Hall where I met many people from different religions and cultures. The SFU Dining Hall consists of all the factors that made the Shrine in Lahore and Multan a place, however, what makes it unique is that it also provides an arena where social norms are contested. The nominal location is the SFU Dining Hall. The absolute location of the Dining Hall is Longitude 49.279956 and Latitude 122.924757 (Google Maps, 2018). Its relative location is between the Residence Office and the Shell Residence Halls. To be more accurate, it is east of the Residence Office, adjacent to it (Google Maps, 2018). From where the SFU Residence Towers and Residence office ends, Dining Hall begins, this is the cognitive location that I developed for the SFU dining.

Location, distance and time given from my Residence (Barabara Rae House) to SFU Dining Hall in Google Map’s (GIS) satellite imagery. (Google Maps, 2018)

The absolute distance from SFU residence to SFU dining Hall is about 100m, and it only takes about a minute or two to reach it, that is its relative distance (Google Maps, 2018). However, since the dining hall is uphill from Residence, going up usually seems longer than going down, so the cognitive distance is more regarding going to the dining Hall than going back to Residence. The social distance in the dining Hall is significant as international students that meet and interact in the dining hall are all from different cultures and social groups, so social distance remains a huge thing. The Dining Hall is accessible as it only requires a minute walk from Residence. Though, those who can not or have not paid for the Dining Hall cannot enter and hence accessibility for them is limited. The utility of the dining Hall is ample. I made more friends through the dining hall that I made in Residence. Moreover, I was able to enjoy entertaining night discussions on various things such as movies, sports, culture, religion.

SFU Dining Hall. (“SFU Dining Services earns”, 2013)

The Dining Hall is a cluster of various cultures. People from East Asia presented different cultural traits by sometimes eating with chopsticks, people from South Asia (from where I belong) offered a different one by eating food that was made exceptionally spicy by things such as hot sauces, people from North America culture ate food that too bland. On cultural nights, clothing showcased different cultural traits such as traditional African and Chinese clothing. Perhaps the most astonishing thing I witnessed was the similarity of culture between the Pakistani Punjabi and Indian Punjabi culture. On cultural nights, the way we danced and the way we talked ( Punjabi language and dialect) was all the same. It was a realisation that Indian Punjab and Pakistani Punjab was a cultural region where, though religion and country was different, the culture was same that was being practised by the majority group. It was in a matter of weeks that I realised that we belonged to the same cultural system. Another appealing thing to discover was the fact that the poetry of Sikh Saints, like Guru Nanak, had a similar old Punjabi essence as I had observed in Hazrat Ganj Baksh poetry. In the exchange of poetry, we realised pretty early as to how much time has changed the Punjabi language. All in all, it was fun to have poetry nights about poetry that we only read, but hardly understood.

Pakistani-style Bhangra. (“Lahore Alumni Celebrate Pakistan Day with “, 2013)

An exciting cultural trait was the dance, Bhangra, we performed. Our dance, though same in its core, had different variations. While the Sikhs and Indian Punjabis jumped around a lot during dancing, ours had less movement of legs and more of forearms. This either turned out to be entertaining or in a debate about who does the correct one. Food also became a centre of dispute as to who ate the spiciest. However, in this case, Pakistani Punjab (our food) was a clear winner. Nevertheless, our proudest cultural trait was the habit of hospitality that we shared. Every time some Punjabi thing was prepared, every Punjabi we saw was called to eat with us. Chai and Tea over board games became custom which went from late nights to early in the mornings. After that, a specific Punjabi food, Halwa Puri, became a particular thing to eat in Surrey on occasional Sundays. All of these were cultural traits that we shared, regardless of religion or nationality.

Indian Bhangra. (“‘Bhangra has become integral”, 2016)

I paid for my SFU dining Hall because I did not know how to cook and the only way for me to get food regularly was through the Dining Hall. The central aim of the SFU dining Hall was to provide food to students who did not know how to cook and hence, in this way, both of us complemented each other. The semester fees that we paid for the dining Hall was too much, coupled up with the residence and tuition fees. However, the dining Hall conserved all the time that I would have wasted in preparing food. Other than the provision of meals, I was able to enjoy the diversity of cultures I witnessed, and rather than seeing my culture being sidelined, my pride and understanding of my own culture increased as I observed more of it. Hence, the transferability was low. The spatial diffusion of my culture was hierarchical as I went on to discuss various aspects of the cultures I learned at SFU dining with my parents back home and they recognised many of the things calling them acts they once used to do. Similarly, I was able to narrate to Indian Punjabis I had befriended in the dining Hall as to how similar our cultural traits were to them and how and why our cultural traits evolved.

In all, the Dining Hall affected me in such a way that I was able to absorb a variety of cultures and develop an understanding of them. The Indian Punjabi culture is a prime example of how we both affected each other’s understanding of culture and the Punjabi language. However, one important event to mention here is that being a fluent Urdu speaker, I was also able to communicate with people from Iran on some level. My Urdu, being more Persian based, became a centre of attention for them because they did not know how much similarities we had, both in language and culture. For me on the other hand, I learned more of the Persian culture and found out the various similarities between our respective cultures. Amongst the similarities, the most astonishing fact was that I had inherited Persian culture too as we both shared the same history of having Turkic or Persian rulers governing us. Learning the Persian language would not come as a surprise to me now.

References;

[Indian-style Bhangra]. (2016, June 05). Retrieved July 23, 2018, from https://www.socialnews.xyz/2016/06/05/bhangra-has-become-integral-part-of-british-music-industry/

[Lahore Alumni Celebrate Pakistan Day with Bhangra-style Flash Mob]. (2013, March 29). Retrieved July 23, 2018, from http://www.pakusalumninetwork.com/2013/03/29/lahore-alumni-celebrate-pakistan-day-with-bhangra-style-flash-mob/

[SFU Dining Hall]. (2013, July 22). Retrieved July 23, 2018, from https://the-peak.ca/2013/07/sfu-dining-services-earns-national-recognition/

Abbas, S. (2016, March 3). Shrine of Hazarat Bahauddin Zakariya [Digital image]. Retrieved July 23, 2018, from https://www.flickr.com/photos/creativenigma/24833913344/in/photostream/

Anjum, M. (2015, March 09). [Urdu Bazaar]. Retrieved July 23, 2018, from https://locallylahore.com/blog/best-shopping-areas-of-lahore/

Express. (2015, November 21). [People of Multan]. Retrieved July 24, 2018, from https://tribune.com.pk/story/995481/776th-anniversary-urs-of-bahauddin-zakariya-concludes/

FLICKR/SMDANISH. (2018, March 29). [Shrine of Baha-ud-Din Zakariya]. Retrieved July 23, 2018, from https://blogs.tribune.com.pk/story/64815/the-city-of-sufism-saints-and-nirvana-multan-has-more-to-offer-than-you-think/

Google. (2018). [Data Darbar Longitude and Latitude]. Retrieved July 23, 2018 from https://goo.gl/maps/X7bdBcCbXcr

Google. (2018). [Google maps direction for driving from my residence to Data Darbar]. Retrieved July 23, 2018 from https://goo.gl/maps/vnP36jwJxmH2

Google. (2018). [Google maps directions for driving from Lahore to Multan]. Retrieved July 23, 2018 from https://goo.gl/maps/8v6Lxf19ro32

Google. (2018). [Google maps directions for walking from SFU Residence to Dining Hall]. Retrieved July 23, 2018 from https://goo.gl/maps/zMnHwYgZLT62

Google. (2018). [Google maps satellite imagery directions for driving from my residence to Data Darbar]. Retrieved July 23, 2018 from https://goo.gl/maps/acDxW4jHfG72

Google. (2018). [Google maps satellite imagery directions for driving from Lahore to Multan]. Retrieved July 23, 2018 from https://goo.gl/maps/iNZGMgxz4kF2

Google. (2018). [Multan Longitude and Latitude]. Retrieved July 23, 2018 from https://goo.gl/maps/52FxEMzkKEx

Google. (2018). [SFU Dining Longitude and Latitude]. Retrieved July 23, 2018 from https://goo.gl/maps/aFbPmcRDvSR2

Lohar, M. (2004, October 05). DAWN – Features; 05 October, 2004. Retrieved from https://www.dawn.com/news/1066533

Nawaz, A. (2014, December 13). [A view of the Data Darbar shrine on the first day of the urs.]. Retrieved July 23, 2018, from https://tribune.com.pk/story/806114/for-the-saint-more-devotees-throng-data-darbar-on-friday/

Official, B. (n.d.). [People of Lahore]. Retrieved July 24, 2018, from https://pk-photography.blogspot.com/2010/11/data-darbar-lahore.html

Shaikh, Z. (November 8, 2010). Sufis under Blue. [Painting]. Retrieved July 24, 2018, from https://zafarshaikh.wordpress.com/2010/11/08/sufis-under-blue-acrylic-on-paper-8x11inch-framed-price800/